Outcome Studies in Education

Growing evidence of the tremendous benefits to be gained from learning to self-regulate emotions and stress at an early age is becoming increasingly apparent. In today’s fast-paced society there is mounting pressure on children to achieve and excel in school at younger and younger ages. Today’s children, however, experience considerably greater stress in their lives, shouldering far greater responsibilities and emotional burdens than youngsters their age did even as few as 10 years ago. Many are part of deteriorating families or households in which parents are rarely home and the responsibility for their and their younger siblings’ care has fallen largely to them. The majority of these children find little more comfort or security at school, where they often fear becoming victims of bullying and violence and feel pressured to engage in sex or consume drugs and alcohol. Increasing media reports of extreme episodes of violence in schools recently have raised public awareness of children’s deteriorating emotional health and underscored the need for more effective solutions to resolve these issues.

“We are educated in school that practice precedes effectiveness, whether in reading, writing, computers, or whatever. We are rarely taught how to practice care, compassion, appreciation or love—essential for family balance.”

Our educational systems continue to focus on honing children’s cognitive skills from the moment they enter the kindergarten classroom. Virtually no emphasis is placed on educating children on managing the inner conflicts and unbalanced emotions they bring with them to school each day. As new concepts such as "social and emotional intelligence" become more widely applied and understood, more educators are realizing that cognitive ability is not the sole or necessarily the most critical determinant of young people’s aptitude for flourishing in today’s society. Proficiency in emotional management, conflict resolution, communication and interpersonal skills is essential for children to develop inner self-security and the ability to effectively deal with the pressures and obstacles that will inevitably arise in their lives. Moreover, increasing evidence is illuminating the link between emotional balance and cognitive performance. Growing numbers of teachers agree that children come to school with so many problems that it is difficult for them to focus on complex mental tasks and the intake of new information, skills that are essential for effective learning. A substantial body of evidence exists that clearly shows when children also learn social and emotional skills, lifelong benefits that cross domains and expand the mind’s capacities can be obtained.

“Some students came to me having memorized the definition of peace, for instance, and they had no idea what it really meant – especially for them personally.”

- In 1940, the top problems in American public schools, according to teachers, were: talking out of turn, chewing gum, making noise, running in the halls and littering. In 1990, teachers identified the top problems as drug abuse, alcohol abuse, pregnancy, suicide and robbery and assault.[293]

- Since 1978, assaults on teachers have risen 700%.[294]

- One youth in six, between the ages of 10 and 17, has seen or knows someone who has been shot.[295]

- A study found that in a group of neglected children, the cortex, or thinking part of the brain, was 20% smaller on average than in a control group.[296]

- Positive emotions have been found to produce faster learning and improved intellectual performance. B. Fredrickson. Rev Gen Psychol. 1998; 2(3)

- In a sample of youth ages 7 to 11 years old in the Pittsburgh, Pa. area, over 20% were determined to have a psychiatric disorder.[297]

- Only 37% of youth report feeling a sense of personal power, and half feel that their life has a purpose.[298]

- Since 1960 the rate at which teenagers commit suicide has more than tripled. Suicide is now the second leading cause of death among adolescents.[299]

- The more teenagers feel loved by their parents and comfortable in their schools, the less likely they are to have early sex, smoke, abuse alcohol or drugs or commit violence or suicide.[300]

Self-Regulation and Reduced Test Anxiety and Increased Test Scores

A grant from the U.S. Department of Education provided funding for a randomized controlled study of 980 10th-grade students in two large high schools. The TestEdge National Demonstration Study (TENDS) was conducted by researchers at HeartMath Institute in collaboration with faculty and graduate students in Claremont Graduate University’s School of Educational Studies. The study’s primary purpose was to investigate the efficacy of the TestEdge program in reducing stress and test anxiety and improving emotional well-being, psychosocial functioning and academic performance in public school students. This involved determining the magnitude, correlates and consequences of stress and test anxiety in a large sample of students and investigating the degree to which the TestEdge program could benefit students in an experimental group, compared to those in a control group. A second programmatic purpose was to characterize the implementation of the program in relation to its receptivity, coordination and administration in a wide variety of school systems with diverse cultural, administrative and situational characteristics.[110, 301]

The study tested two major hypotheses. The first is that competence in the emotion self-regulation skills taught in the TestEdge program would result in significant reductions in test anxiety, which, in turn, would generate a corresponding improvement in academic and test performance. Secondly, as a result of the improvement in student self-regulation skills, it was hypothesized there would be improvements in stress management, emotional stability, relationships, overall student well-being, and in classroom climate, organization and function. To investigate these hypotheses, two studies were conducted, each with different research objectives and designs.

Primary Study

The primary study focused on an in-depth investigation of the entire 10th-grade populations at two large California high schools. One high school was randomly selected as the intervention school, while the other served as the control school. This was designed as a quasi-experimental, longitudinal field study involving pre- and post-intervention measures within a multimethods framework. Extensive quantitative and qualitative data were gathered using a questionnaire developed and validated for the study, interviews and structured observation, and student test scores from California standardized tests – the California High School Exit Examination (CAHSEE) and the California Standards Test (CST). Altogether, 980 students participated in the primary study, of which 636 (53% male, 47% female) were in the experimental group and 344 (40% male, 60% female) were in the control group.

The TestEdge program was taught by English teachers over one semester for approximately four months. In the program, students learned and practiced specific emotion-management techniques to aid them in more effectively handling stress and challenges, both at school and in their personal lives. They also were taught how to apply these techniques to enhance various aspects of the learning process, including test preparation and test-taking. Both the student and teacher programs included use of the Freeze-Framer (now emWave Pro) technology, a heart-rhythm coherence feedback system designed to facilitate acquisition and internalization of the self-regulation skills that were taught.

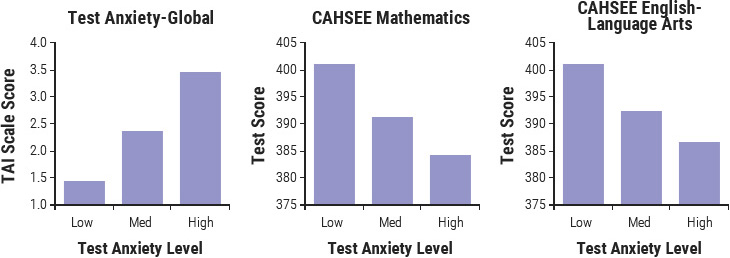

Across the whole sample at baseline, 61% of all students reported (Spielberger test-anxiety inventory) being affected by test anxiety, with 26% experiencing high levels of test anxiety often or most of the time. Twice as many females as males experienced high levels of test anxiety. There was a strong negative relationship between test anxiety and test performance; students with high levels of test anxiety scored, on average, 15 points lower on standardized tests in both mathematics and English-language arts (ELA) than students with low test anxiety (Figure 9.1). A multiple regression analysis found that affective mood measures accounted for the wide variance between student test performance on both the CST and CAHSEE English-language arts exams and Test Anxiety Inventory – global scale (23% versus ~13%, respectively). Positive feelings and prosocial behaviors were found to have positive effects on test performance, while strongly negative feelings and antisocial behaviors had negative effects.[302] Taken as a whole, these findings are sobering and justify the concern that student test anxiety and emotional stress may significantly jeopardize assessment validity and therefore may constitute a major source of test bias.

There was a significant reduction in the mean level of test anxiety. Of those students at the intervention school who had reported being affected by test anxiety at the beginning of the study, 75% had reduced levels of test anxiety by the end of the study. This reduction in test anxiety also was evident in more than three-quarters of all classrooms, and it was observed throughout the academic ability spectrum, from high test-performing classes to low test-performing classes.

Figure 9.1 Baseline test anxiety, measured by the Test Anxiety Inventory (TAI) – global scale score and California High School Exit Examination (CAHSEE) scores in English-language arts and mathematics have been classified into three approximately equal-sized groupings of students with low, medium, and high test anxiety scores. A strong, statistically significant (p < 0.001) negative relationship is clearly apparent between mean level of test-anxiety and mean performance on the standardized tests: As test anxiety increases, test performance decreases.

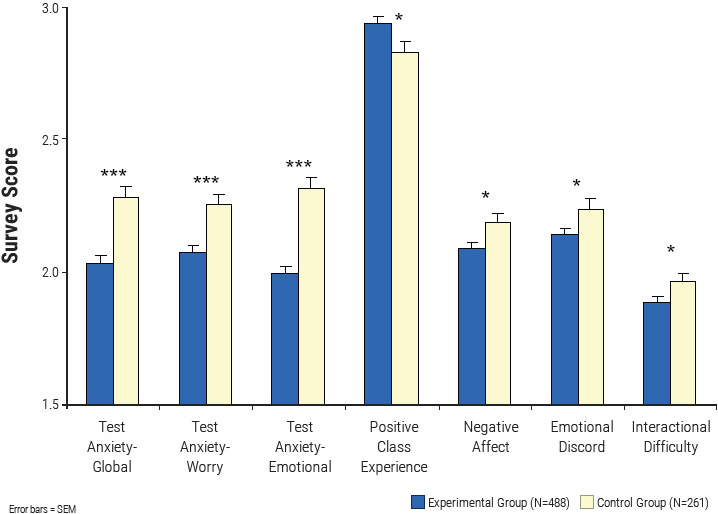

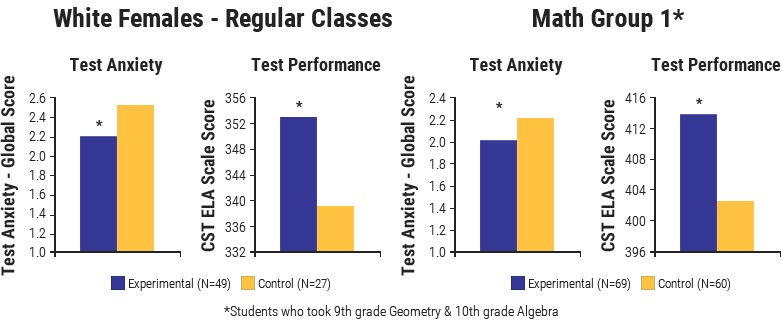

After the TestEdge program was provided to the students in the intervention school, there was strong, consistent evidence of a positive effect from the intervention on these students, compared to those in the control school. The reduction in test anxiety was associated with significant improvements in social and emotional measures (Figure 9.2), including reductions in negative affect, emotional discord and interactional difficulty, and an increase in positive class experience. In four matched-group comparisons (involving subsamples of 50 to 129 students per grouping), there was a significant increase in test performance in the experimental group over the control group, ranging on average from 10 to 25 points. In two of these matched-group comparisons, this significant increase in test performance was associated with a significant decrease in test anxiety in the experimental group (Figure 9.3).

“As annual testing becomes a regular part of our educational system through the No Child Left Behind Act and other state requirements, it is important that when we test students on their mastery of a subject, we are truly getting accurate results. The program developed by HeartMath Institute to reduce test-related anxiety shows great potential for helping students achieve success.”

Figure 9.2 Results of an ANCOVA of pre– and post-intervention changes in measures of test anxiety (global scale, worry component, and emotionality component) and social and emotional scales (positive class experience, negative affect, emotional discord, and interactional difficulty) showing significant differences between the intervention and control schools. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 9.3 ANCOVA results for two subsamples from the intervention and control schools matched on sociodemographic factors (White females in average academic-level classes) and ninth-grade math-test performance (Math Group 1), respectively. For these matched-group comparisons, significant reductions in test anxiety in conjunction with significant improvements in test performance (California Standards Test – English-language arts) were observed in the experimental group, compared to the control group. *p < 0.05.

Student participants describe how they apply HeartMath skills in various areas of their lives:

"I use HeartMath every day before math class. This helps me understand the concepts and grasp them more easily."

"HeartMath has obviously helped in my algebra II class. On the last test, using HeartMath, I scored a 97%. It really calmed me down and opened my mind to clearer thinking."

"Working at Coney Island, I’m around people all the time; being an assistant manager, the questions, concerns and complaints all come to me. In order to answer them or handle the situation without taking it personally, I use HeartMath. It’s helped calm my nerves a lot."

"Sometimes during sports activities I get mad at myself and do very badly. One time I used HeartMath and I let all of my stress go and just had fun. In the end, I performed better than I expected."

"I have used HeartMath during band. I hate the feeling of having to play a hard part in front of the whole band by myself. I get so nervous sometimes that my hands shake and my mind goes blank. … Using HeartMath, I have seen a significant improvement in my playing alone in front of people."

"I use HeartMath during any stressful encounter I have, whether at home, school, with my parents or with friends. Anytime I get frustrated or upset, I try to practice (HeartMath techniques) and focus from head to heart."

"(One) time, I was taking a test in Chemistry, and I could not remember the equation for the test. I had three minutes left and I used one of those minutes to do HeartMath. … I ended up getting a 90% on the test and brought my chem grade up."

"(One) instance was a presentation in English class. I am a shy, solitary person and I sometimes get very stressed with presentations. However, I used what I learned from HeartMath and was able to present my topic efficiently."

"Whenever I email or write my boyfriend, who recently left to work in Utah over the summer, I use HeartMath to calm down and say what I want to say without sounding angry, upset – and (not) panic."

Physiological Study Findings

In addition, a physiological substudy was conducted on a randomly stratified sample of students from both schools. Utilizing measures of heart rate variability (HRV), this controlled laboratory experiment investigated the degree to which students had learned the skills taught in the TestEdge program using an objective measurement of their ability to shift into the physiological coherence state before taking a stressful test.[110]

In a controlled experiment simulating a stressful testing situation, students from the intervention and control schools (N = 136) completed a computerized version of the Stroop color-word conflict test (a standard protocol used to induce psychological stress), while continuous heart rate variability recordings were gathered. For the pre-intervention administration of the experiment, after a resting HRV baseline had been collected, students were instructed to mentally and emotionally prepare themselves to perform an upcoming challenging test and activity, after which they participated in the Stroop test. They also were told if they performed well on the test, they would be given a free movie pass. The same procedures were used in the post-intervention assessment.

Results from the post-intervention physiological experiment:

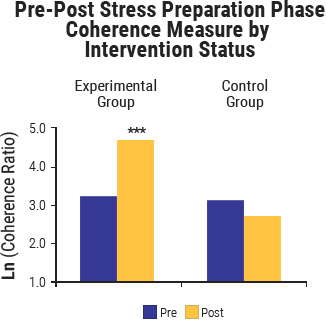

- The HRV data indicated students who had received the TestEdge program had learned how to better manage their emotions and to self-activate the physiological coherence state under stressful conditions during the stress-preparation segment of the protocol (Figure 9.4).

- The ability to self-activate coherence noted above was associated with significant reductions in test anxiety and corresponding improvements in measures of emotional disposition.

- For students matched on baseline test scores, the capacity to self-activate coherence was associated with a reduction in test anxiety as well as an improvement in test scores in the experimental group (Figure 5.1). This finding is consistent with the results for students in the larger study.

- Students in the experimental group also exhibited increased heart rate variability and heart-rhythm coherence during the resting baseline period in the post-intervention experiment – even without conscious use of the self-regulation techniques. This suggests that through consistent use of the coherence-building tools over the study period, these students had internalized their benefits, thus instantiating a healthier, more harmonious and more adaptive pattern of psychophysiological functioning as a new set-point or norm.

Figure 9.4 These data are from the physiological study, a controlled experiment involving a random stratified sample of students from the intervention and control schools (N = 50 and 48, respectively). These graphs quantify heart-rhythm coherence, the key marker of the psychophysiological coherence state, during the stress-preparation phase of the protocol. Data are shown from recordings collected before and after the TestEdge program. The experimental group demonstrated a significant increase in heart-rhythm coherence in the post-intervention recording when they used one of the self-regulation techniques to prepare for the upcoming stressful test – compared to the control group. ***p < 0.001.

Qualitative Findings:

To supplement the quantitative data, the study gathered observations of student classroom interactions in the two schools and conducted structured interviews with teachers. The pre- and post-observational findings were broadly consistent with the findings from the quantitative analysis:

- More positive changes were observed in the social and emotional environment and interaction patterns in the classrooms of the experimental school, while more negative changes were observed in the control school over the course of the semester.

- Students at the experimental school exhibited reduced levels of fear, frustration and impulsivity. They also exhibited increased engagement in class activities, emotional bonding, humor, persistence and empathetic listening and understanding.

- Most teachers acknowledged in interviews that their students came to school emotionally unprepared to learn, but they felt their own educational training did not equip them with the requisite skills to effectively manage their personal stress or to help their students manage their stress. Teachers were supportive of integrating emotion-management instruction into educational curricula. Most reported experiencing personal benefits as well as observing positive changes in their students’ behavior as a result of the intervention program.

Secondary Study

The secondary study consisted of a series of qualitative investigations to evaluate the accessibility, receptivity, coordination and administration of the program across elementary, middle and high schools and in school systems with diverse ethnic, cultural, socioeconomic, administrative and situational characteristics. We employed a case-study approach to evaluate the implementation of the TestEdge program in nine schools in eight states (California, Delaware, Florida, Ohio, Maryland, Texas, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania). Age-appropriate versions of the TestEdge program were delivered to selected classrooms, covering the third through eighth and 10th grades.

Observational and interview data were gathered to provide information on best practices and potential difficulties when implementing interventions such as TestEdge in widely diverse school settings.

Major Findings from the Secondary Study

Evaluation of the implementation case studies of the TestEdge program, conducted in selected classrooms at various grade levels across different states, produced a number of notable results and largely corroborated the findings from the primary study:

- In teacher interviews, the lack of emotion- and self-management education for students was seen as a significant obstacle to learning and academic performance. Most teachers described positive changes in students’ attitudes, behaviors, test anxiety and academic performance, and attributed these to the TestEdge program. They also felt that the tools and skills that were learned would have a positive impact on their students’ future social, emotional and academic development.

- Most teachers reported that the program provided substantial benefits in their personal and professional lives.

- In general, the program’s implementation was more successful when there were several teachers at the same grade level teaching it and when teachers were able to internalize the use of the tools in their own lives.

- Major challenges to successful program implementation included inadequate class time; logistical problems encountered with school administration; and securing the support of the principal and other school administrators to foster teacher commitment.

Elementary School Case Study:

A case example of highly successful implementation of the TestEdge program was provided by an in-depth study conducted at the third-grade level in a Southern California elementary school. Several notable findings emerged from the study:

- Large increases in state-mandated test scores were observed, which far exceeded academic targets for the year. As a result, student proficiency grew from 26% to 47% in English-language arts and from 60% to 71% in mathematics.

- Corresponding emotional and behavioral improvements also were observed among students in the classrooms.

- The success of implementation was largely the result of the enthusiastic support provided by the school’s principal and key teachers and administrators.

Conclusion

Overall, the evidence from this rich combination of physiological, quantitative, and qualitative data indicates that the self-regulation skills and practices taught in the TestEdge program led to a number of important successes. It is our hope that the results of this research will have an impact on policies regarding the importance of integrating stress and emotion self-management education into school curricula for students of all ages. By introducing and sustaining appropriate programs and strategies, it should be possible to significantly reduce the stress and anxiety that impede student performance, undermine teacherstudent relationships and cause physiological and emotional harm. Such programs have the promise of increasing the effectiveness of our educational system and, in the long-term, boosting the academic standing of the United States in the international community.

Evaluation of HeartMath Program with Schoolchildren in West Belfast

A study was conducted in Belfast, Ireland to investigate the efficacy of a HeartMath program as a means of improving student emotion self-regulation and associated improvements in emotional stability, relationships and overall student well-being.[303] Seven schools were chosen for the study: three were primary schools (n = 122) and four were post-primary schools (n = 121). Two or three classes from each school participated in the study. Each class participated in a one-day interactive program in which they learned how to use the HRV coherence system (emWave Pro) and was taught an emotion self-regulation technique. The students and teachers also were provided with an audio CD called "Journey to my Safe Place" to lead them through a self-regulation exercise at later times. Teachers were encouraged to allow the students to use the games on the emWave once or twice weekly, as time permitted. The outcome measure was the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaires (SDQ) for ages 4 to 16; these were completed pre- and post-intervention by the teachers.

Based on the SDQ scales, the primary students showed a statistically significant reduction in emotional problems (51%); conduct problems (43%); hyperactivity (40%); and a significant improvement in relating to peers (50%). According to the scales, postprimary students had significant reductions in hyperactivity (12%), emotional problems (9%) and conduct problems (9%), and they showed (27%) improvement in relating to peers. As expected, the primary children benefitted more than post-primary students, and the authors suggest this may be the result of better adherence to utilizing the skills, which are easier to reinforce in primary-school students because they are in the same classroom each day. In contrast, the students in the post-primary schools move from class to class throughout the day, so it was more difficult to set up a routine to support the intervention. In addition, most of the primary-school classes began the study several weeks before the post-primary classes, which gave them more time to plan how the program would be integrated into their classes.

Self-Regulation for Promoting Development in Preschool Children

The importance of children learning effective social and emotional skills at an early age cannot be overestimated. A large body of research clearly shows that learning how to process and self-regulate emotional experience in infancy and early childhood not only facilitates neurological growth, but also determines the potential for subsequent psychosocial and cognitive development. Conversely, the inability to appropriately self-regulate feelings and emotions can have devastating long-term consequences in a child’s life, impeding development and often resulting in impulsive and aggressive behavior, attentional and learning difficulties and an inability to engage in prosocial relationships. Furthermore, this early deficiency is associated with later-forming psychosocial dysfunction and pathology that not only robs individuals of a fulfilling life, but also results in an enormous cost to our society.[80]

The HeartMath Institute developed a program called Early HeartSmarts® (EHS) specifically intended to help equip children aged 3 to 6 with the foundational emotion self-regulation and social competencies for school. The program trains teachers to guide children in learning emotion self-regulation and key, age-appropriate social and emotional skills, toward a goal of promoting children’s emotional, social, and cognitive development. The Early HeartSmarts program included interactive activities, games and self-management tools designed to promote children’s learning of several key emotional and social competencies, which in turn are known to promote psychosocial development. These included:

- How to recognize and better understand basic emotional states.

- How to self-regulate emotions.

- Ways to strengthen the expression of positive feelings.

- Ways to improve peer relations.

- Skills for developing problem-solving.

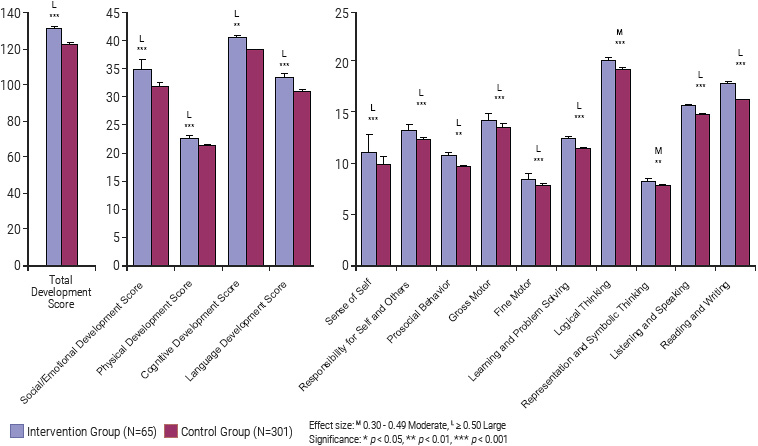

A study was conducted in the Salt Lake City School District to evaluate the efficacy of the Early HeartSmarts program.[304] The study was conducted over the school year using a quasi-experimental longitudinal field research design with three measurement moments (baseline and pre- and post-intervention panels). Children in 19 preschool classrooms at 19 schools were divided into intervention and control group samples (N = 66 and 309, respectively; mean age = 3.6 years). Classes in the intervention group were selected by the district to target children of lower socioeconomic and ethnic minority backgrounds. The Creative Curriculum Assessment (TCCA), a teacher-scored, 50-item instrument, was used to measure student growth in four areas of development: social/emotional, physical, cognitive and language development.

Teachers delivered the program to their students throughout the second half of the school year. A key element of the program was learning and practicing two simple HeartMath emotion-shifting tools: Shift and Shine and Heart Warmer.

Overall, results provided compelling evidence of the efficacy of the EHS program increasing total psychosocial development and each of the four development areas measured by the Creative Curriculum Assessment: The results of a series of ANCOVAs found a strong, consistent pattern of large, significant differences on the development measures favoring preschool children who received the EHS program over those in the control group (see Figure 9.5). From the adjusted means on the five development scales, a significant difference with a large effect size was observed favoring the intervention group on the total development scale (ES 0.81, p < 0.001), and on each of the social/emotional development (ES 0.97, p < 0.001), physical development (ES 0.79, p < 0.001), cognitive development (ES 0.55, p < 0.01), and language development (ES 0.73 p < 0.001) scales. And at the subcomponent level (right-hand graph in Figure 9.5), the intervention group demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in all 10 constructs, eight of which showed differences that were large in terms of effect size. The magnitude of development observed for the intervention-group children is particularly striking, considering that initial measurements indicated that at the beginning of the study, they started with a significant development handicap relative to their peers in the control group. After participating in the EHS program, they had surpassed the control group’s development growth by the end of the study. A further important finding, from an analysis of demographic factors, was that the program was effective in promoting development in children across all the sociodemographic categories investigated: males, females, Hispanic, Caucasian, free lunch (an indicator of low socioeconomic status) and no free lunch.

An important point to emphasize is that these results are for preschool children, who are very young, and 96% of them were 3.0 to 4.0 years old. It is both striking and remarkable that children as young as 3 can begin to learn and practice the emotion self-regulation skills, which appears to promote their development across a wide range of categories. Given that the age range from 3 to 6 years is a period of accelerated neurological growth and development, it is likely that the learning and sustained use of these skills and practices during this important developmental period will readily instantiate a new set point in a young child’s nervous system for an optimal pattern of emotion self-regulation and healthy social function, thereby significantly boosting the development trajectory of future prosocial behaviors and academic achievement.

Figure 9.5 Adjusted means showing results of ANCOVA of intervention effects on development measures comparing intervention and control groups.

Reduced Burnout in College Students

Dr. Ross May and colleagues at Florida State University have found that the psychophysiological functioning underlying school burnout is of particular importance. Their research has shown student burnout is associated with increased markers of cardiovascular risk and poor academic performance (GPA).[305, 306] They suggest that because school burnout is associated with increased cardiac risk, it should be recognized as a potential public health issue and a cause for concern for university officials. This is especially true because cardiovascular disease (CVD), including hypertension, coronary heart disease, heart failure, peripheral artery disease and stroke, is the most salient cause of death in the United States and the rest of the world. The cardiovascular responses seen from individuals suffering from higher levels of burnout have been identified as risk factors for the future development of cardiovascular disease.[307-309] They also have demonstrated that school burnout is a stronger predictor of GPA than anxiety and depression.

May and his colleagues conducted a study comparing the effects of training in HeartMath self-regulation techniques, supported by HRV coherence training, with high-intensity aerobic training (HIIT); both types of training were intended to ameliorate school burnout in undergraduate students. A total of 90 participants (freshman year, mean age = 18.55, SD = 0.99, 82% female) were randomly assigned to one of the following three groups: one that received the HeartMath Building Personal Resilience program, which included learning self-regulation techniques and HeartMath’s computerbased HRV coherence training devices (emWave), high-intensity aerobic training and a no-intervention control. All of the groups were evaluated for cognitive, psychological and cardiovascular functioning before and after a four-week intervention period. The ethnic composition of the sample was 70% Caucasian, 7% African American, 13% Hispanic, 7% Asian and 3% undisclosed ethnicity.

All participants completed a physical health history questionnaire, the School Burnout Inventory (SBI), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), and a self-reported sleep quality questionnaire. In addition, academic absenteeism (how many classes were missed over the semester) and GPA were assessed. Cognitive functioning was assessed with computerized working-memory span measure versions of the common reading and operation working memory span tasks.[310, 311] The span tasks require participants to remember target letters while performing a concurrent reading comprehension (reading span) or arithmetic task (operation span). The number of targets in a trial set varied between two and five, with three trials of each size for each of the tests. Physical fitness with a stationary bike test and V02 max and cardiovascular functioning were assessed by measures of aortic hemodynamics, beat-to-beat blood pressure, and heart rate variability.

The HeartMath resilience training and HRV coherence sessions were conducted at the university wellness center by trained student instructors three times per week over a four-week period. Each student practiced shifting and sustaining heart-rhythm coherence while using an emWave device and was encouraged to use the techniques and device on a regular basis to help them improve their self-regulation skills and physiological and psychological balance. The high-intensity interval training (HIIT) comprises brief bursts of intense exercise separated by short periods of recovery. This method of exercise is a time-efficient stimulus to induce physiological adaptations normally associated with continuous moderate-intensity training.[312] As few as six sessions of HIIT over two weeks has been shown to increase muscle oxidative capacity to the same extent as a continuous moderate-intensity training protocol that requires an approximately threefold greater time commitment and approximately ninefold higher training volume.[313] The HIIT training sessions were conducted at the university wellness center by trained instructors three times per week over four weeks. The control group visited the wellness center to report their normal daily activities for the duration of the study. Participants were encouraged to not change their normal daily routines.

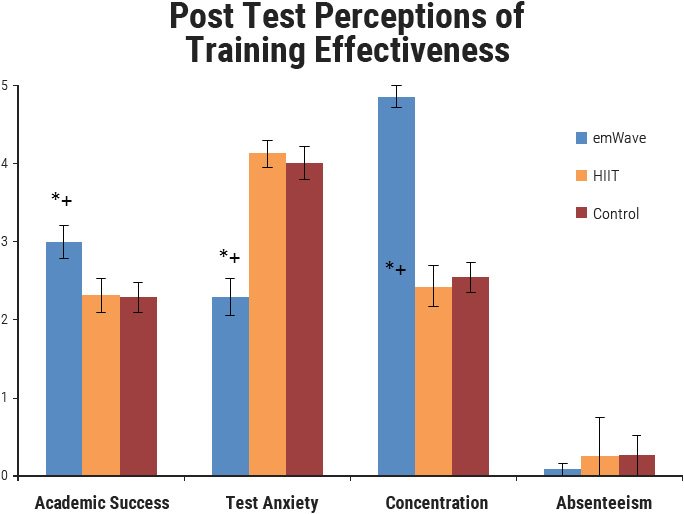

In comparison to HIIT and control, the HeartMath group participants had significant improvements in academic success and concentration and significant decreases in test anxiety and absenteeism (Figure 9.6).

Figure 9.6 Shows the data for the three groups for academic success, test anxiety, concentration and absenteeism from classes over the semester. Data are mean and 95% CI. * = p < .05 HeartMath vs. HIIT posttest, + = p < .05 HeartMath vs. Control, a = p < .05 HeartMath pretest vs. HeartMath posttest, b = p < .05 HIIT pretest vs. HIIT posttest, c = p < .05 Control pretest vs. Control posttest.

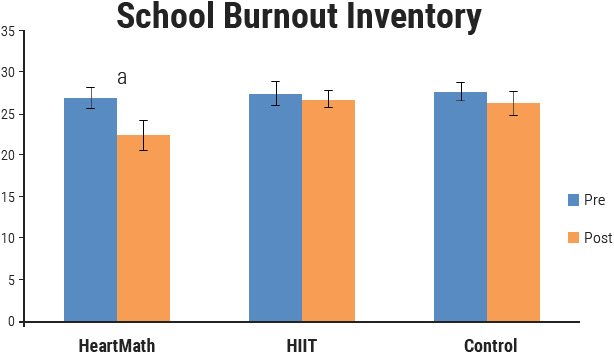

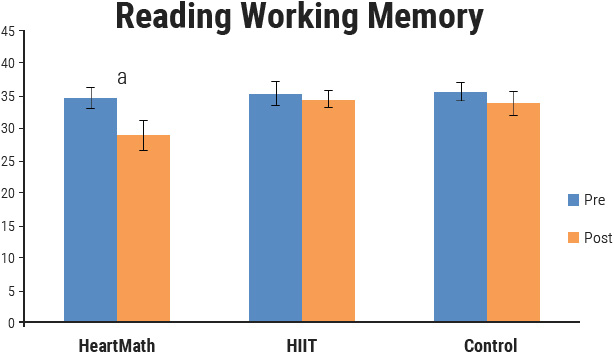

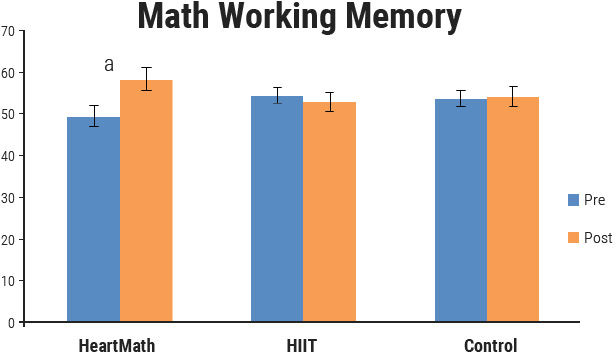

The HeartMath group also was the only group to show a significant reduction in school burnout from the pretests to posttests (Figure 9.7) and significant improvements in the cognitive functioning assessments of reading and operational span working memory capacity from the pretests to posttests (Figure 9.8 and 9).

Figure 9.7 Shows the pre- and post-data for the three groups for school burnout. Data are mean and 95% CI a = p < .05 HeartMath pretest vs. HeartMath posttest.

Figure 9.8 Shows the pretest and posttest data for the three groups for reading working memory. Data are mean and 95% CI a = p < .05 HeartMath pretest vs. HeartMath posttest.

Figure 9.9 shows the pretest and posttest data for the three groups for math working memory. Data are mean and 95% CI a = p < .05 HeartMath pretest vs. HeartMath posttest.

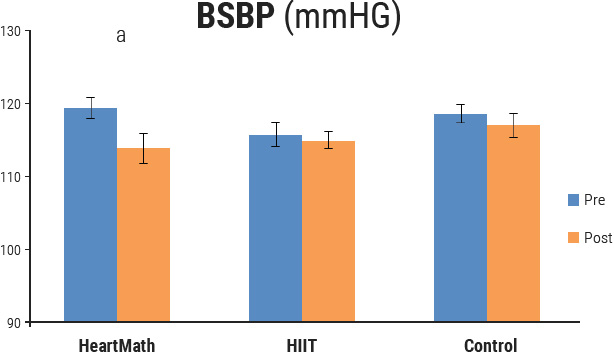

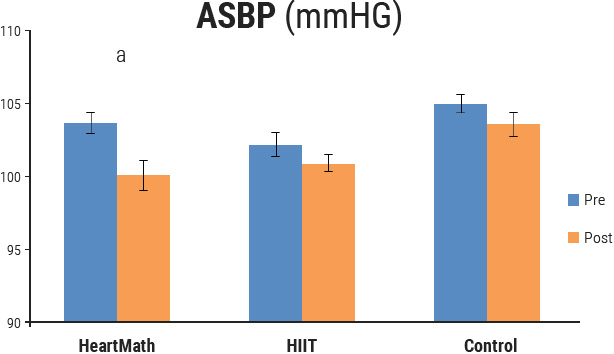

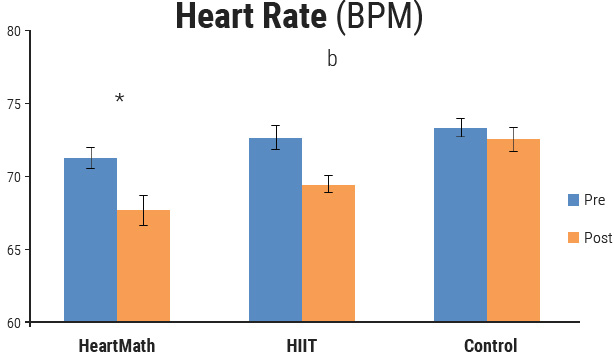

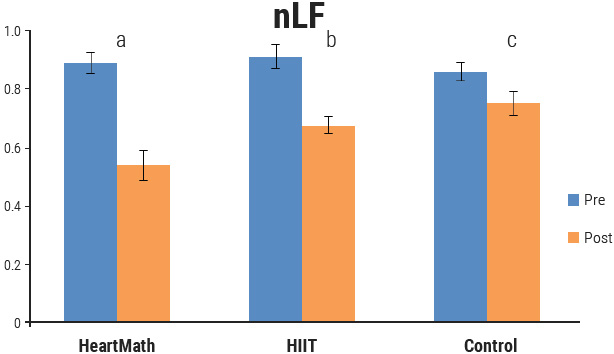

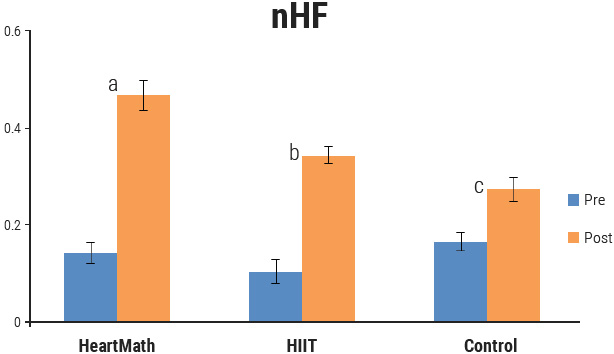

In terms of cardiovascular functioning, the HeartMath group showed significantly decreased brachial and aortic blood pressure, and both the HeartMath and HIIT groups had significantly decreased heart rate from pretest to posttest (Figure 9.10, 11 and 12). The HRV metrics showed that the normalized LF power was significantly lower in the post-assessment measures, compared to the pre-intervention measures, and HF power was significantly increased in all three groups (Figures 9.13 and 14). In addition, the HIIT group was the only group to show significantly improved VO2 max.

Figure 9.10 Brachial systolic blood pressure (BSBP) data for the three groups. Data are mean and 95% CI. a = p < .05 HeartMath pretest vs. HeartMath posttest.

Figure 9.11 Aortic systolic blood pressure (ASBP) data for the three groups. Data are mean and 95% CI a = p < .05 HeartMath pretest vs. HeartMath posttest.

Figure 9.12 Heart-rate data for the three groups. Data are mean and 95% CI. * = p < .05 HeartMath vs. HIIT, b = p < .05 HIIT pretest vs. HIIT posttest.

Figure 9.13 Normalized low frequency power data for the three groups. Data are mean and 95% CI. a = p < .05 HeartMath pretest vs. HeartMath posttest, b = p < .05 HIIT pretest vs. HIIT posttest, c = p < .05 Control pretest vs. Control posttest.

Figure 9.14 Normalized high frequency power data for the three groups. Data are mean and 95% CI. a = p < .05 HeartMath pretest vs. HeartMath posttest, b = p < .05 HIIT pretest vs. HIIT posttest, c = p < .05 Control pretest vs. Control posttest.

Coherent Learning: Creating High-level Performance and Cultural Empathy From Student to Expert

Nursing schools are charged with graduating nursing students who reflect the race and ethnicity of the communities those schools serve. In 1998, 19 Native American students were admitted to the University of Oklahoma College of Nursing. Only 12 had graduated two years later. The rate of attrition for Native American nursing students averaged 57% between 1997 and 2001, compared to the overall attrition rate of approximately 9%.

The OU College of Nursing identified staff members to become certified in a HeartMath program in 2002. The program was implemented starting in 2003. Participation in the program was voluntary for the first year, but it became part of the new-student orientation the next year. Training was offered monthly for students and faculty and was available to every student. Laboratory computers were equipped with the HRV coherence training technology to support the self-regulation skills so students could practice during school hours. Several faculty members also provided student mentoring and practiced with students in their offices at students’ request. Many faculty members gave short sessions for the students on how to do the self-regulation techniques before taking tests.

Although only Native American students are reported here, students from all ethnicities and races reported benefits. Based on test results for all students, it was determined that practicing the HeartMath techniques increased test scores by an average of 17 points. Following implementation of the HeartMath selfregulation tools in 2003, the average attrition rate for Native American nursing students between 2003 and 2008 was 37%, compared to the 57% attrition rate in the 1997-2001 period. During this time, requirements for admission and graduation became more stringent and required increased testing. From the start of the program through 2006, the overall attrition rate for the school dropped from the 9% reported in 2001, varied from 3% or less. Use of HeartMath while in the school helped decreased the attrition rate by about 35% for Native American students from 2003 to 2008.

Students reported increased confidence in their testtaking abilities and reported fewer physical health issues, which they attributed to the regular practice of the self-regulation skills they learned.

In addition, the Native American nursing students using the stress-reducing practices demonstrated improved test-taking and perceived physical health and higher graduation rates than those who did not use them.[314]

Improving Learning and Math Proficiency in College Students

A major challenge in our current educational system is the significant number of students entering college who do not meet the basic minimum academic requirements for enrolling in college-level courses.

These students must take remedial courses in core academic subjects before they are ready to enter regular college classes. Personnel at the University of Cincinnati Clermont College (UCCC) have observed that as many as 92% of incoming first-year college students score below standards for college-level mathematics. As a result, students have difficulty succeeding in their required mathematics courses. UCCC and the Greater Cincinnati Tech Prep Consortium have formed a partnership to help solve this problem, with the goal of reducing the need for remediation in math. Working with this program, UCCC professors Drs. Michael Vislocky in mathematics and Ron Leslie in psychology pioneered a new approach.[315]

They integrated HeartMath’s self-regulation techniques and heart-rhythm coherence feedback technology into college prep readiness programs in math. The goal of these programs was to reduce high school students’ anxiety related to learning math and taking high-stakes tests and thereby improve students’ learning, comprehension and retention.

“Lots of people are afraid of math. Learning to center in stressful situations can help these students perform better on tests, and it also opens up their life choices. So many people will switch majors just to avoid a specific math class.”

The following elements were included in the training: 1) Discussion of the physiology of emotions. 2) Discussion of core values and engaging students in experiences that allowed them to practice sharing heartfelt emotions emerging from their core values. 3) Practice moving from the state of thinking about positive emotional experiences to actually experiencing those emotions. 4) Gaining self-awareness of emotional shifts. 5) Working in small groups to build a sense of community in order to become comfortable generating and sharing positive emotions. The overall goal of this instruction was to introduce students to the relationship between emotions and cognitive performance. To assess changes in math performance, each class of students took the Compass college placement test in mathematics at the beginning and end of the three-week program.

Heart-rhythm coherence feedback using the Freeze-Framer (now called emWave Pro) while simultaneously working on math problems was a key element of the program. In these sessions, students were able to observe their reactions to difficult problems, as reflected in the HRV feedback, thereby gaining more insight into their emotional responses and how to self-regulate them. They practiced self-activating coherence and using their intuition to find ways to solve math problems.

Students were extremely responsive to the program, and results over the years continuously improved as the professors discovered new ways to integrate and sustain students’ use of the self-regulation techniques. In the first year the professors integrated HeartMath techniques, they found an average increase of 19% in math scores, which had increased to 24% gains by the third year in Compass test scores, compared to classes that had not integrated the selfregulation techniques. These gains were notable given the program’s short duration and its primary focus on emotion-management skills rather than on formal math instruction.

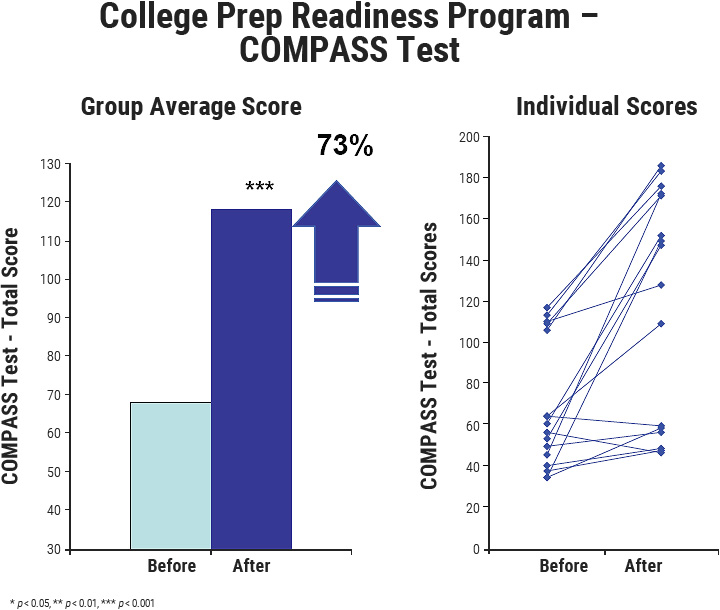

In the fourth year, use of the self-regulation techniques and other HeartMath practices became fully integrated into the classroom program and produced the best results of all four years, far exceeding even the instructors’ expectations. These results are shown in Figure 9.6, which compares students’ scores on the Compass college placement test in Algebra before the program and seven weeks later, after learning and using the techniques and HRV coherence technology as an integrated part of their math instruction. The results showed a significant (p < 0.001) improvement with an average increase of 73% in student math scores.

Figure 9.15 The average and individual student improvements in scores on the Compass college placement test in algebra before and seven weeks after learning and using the HeartMath self-regulation skills and HRV coherence technology as an integrated part of math instruction. Results show a statistically significant (p < 0.001) average increase of 73% in student scores on the college placement test.

The college prep readiness program was then expanded in following years with the intent of eliminating the need for students to have to take math remediation classes. With the support of a high school principal and math teacher, the program was integrated into an 11th grade math class at a local high school. Guided by the program instructors, 16 students and their math teacher learned the tools of the HeartMath System. The teacher guided the students in using the HeartMath techniques as an integral part of the class and homework. Four Freeze-Framer stations were set up in the classroom and students practiced using it by rotating throughout the class period.

“I’m ecstatic! High school students are excited about this program because it gives them an edge in learning math and in demonstrating their proficiency on tests. Many students who felt discouraged about their math performance now feel confident that they can succeed.”

Drs. Vislocky and Leslie observed:

"There was a seamless integration of learning math and HeartMath infused with the curriculum in the context of the classroom setting. The teacher internalized and facilitated the HeartMath process, and actively engaged students in the learning process. The teacher got the students personally involved by giving assignments and journaling their HeartMath experiences. This provided opportunities to make continuous improvements based on feedback from students. Students were confident that their input was valued and acted upon through adjustments in the classroom."

Key factors that appear to maximize the success of the program:

- Committed teacher/facilitator.

- High expectations for student success.

- Managing emotions should take place in the context of the classroom

- Journaling or some mechanism for feedback to make continuous improvements along the way.

- Begin program at the beginning of the school year.

- Train the teacher/facilitator.

- Students must be provided with ample opportunities to apply HeartMath tools inside and outside the classroom.

- Real classroom experiences using HeartMath tools so individuals realize direct benefits.

- Integration of HeartMath in the classroom is important for promoting student-to-student interaction.

Drs. Vislocky and Leslie’s work represented the first effort we knew of to integrate the HeartMath System of self-regulation tools directly into a mathematics learning environment. The findings provided strong evidence that the integration of coherence-building tools and technologies into the instruction of core academic subjects could be an effective way to enhance student learning and academic performance and to better prepare high school students for entry into higher education.